3-minute read - by Sander Hofman, December 22, 2015

Moore’s Law’s exponential growth in computing power is enabling the development of smarter robots, self-driving cars and autonomous drones. But gloomy scenarios in popular culture fuel our fears that the continuous development of artificial intelligence (AI) might one day lead to the end of human civilization at the hand of our own superintelligent creation. And if Stephen Hawking, Bill Gates and Elon Musk worry about it, why shouldn’t we?

“If superintelligence takes over, a 'Moore’s Law company' like ASML would surely carry part of the blame,” Pim Haselager says with a wink. But the associate professor of artificial intelligence at the Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, is quick to add: “Let’s not get paranoid. Even though computational speed might increase rapidly for many years to come, it’s highly questionable whether our capacity to build better models of cognition increases at the same speed. There’s a famous quote in AI land: ‘If our brain was so simple that we could understand it, we would be so stupid that we couldn’t.’”

“If our brain was so simple that we could understand it, we would be so stupid that we couldn’t.”

In November 2015, Haselager spoke to a packed auditorium on the ASML campus in Veldhoven, the Netherlands. Some 150 scientists and engineers had come to hear him discuss Nick Bostrom’s book ‘Superintelligence’ in an ASML Tech Talk, a series of science- and technology-focused talks running since 2009.

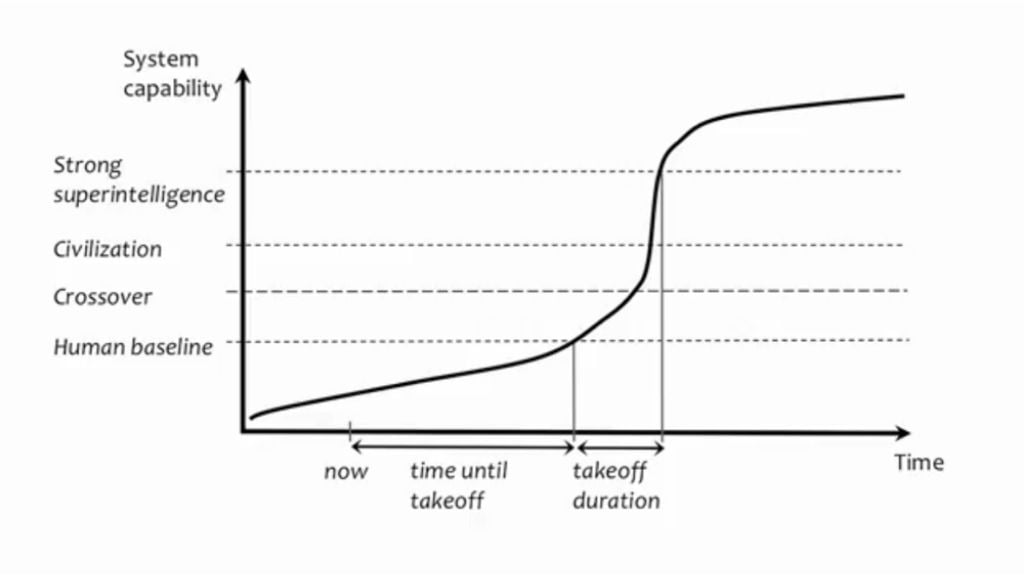

“What is clear is that the question about the relationship between artificial intelligence and human intelligence is becoming inevitable,” Haselager says, showing a graph that Bostrom calls the ‘intelligence explosion’.

“There’s a moment in time called the 'cross-over point', when artificial intelligence supersedes human intelligence and becomes superintelligence,” Haselager says. “But when it’s infinitely smarter than us, how could we grasp the possibilities and dangers that superintelligence may pose? We’re at the point that this has become a topic of societal debate. It’s our job as AI researchers to think about what could and is most likely to happen. Because who else could do a better job?”

Haselager has a clear stance in the debate: he believes that the emphasis is wrong. “We focus on intelligence because we pride ourselves on it. It’s what we think distinguishes us from other species. So we want to magnify it. But what does it mean to be an intelligent being? It’s about more than problem solving and task execution. Cognition, feeling, sentience and morality are all part of it, but research on these topics is not progressing exponentially like computing power.”

By refocusing AI research programs, Haselager thinks we will gain a more rounded understanding of intelligence. This could help tackle social challenges. He points to the example of robots. “It’s clear that AI-driven robots will take a prominent role as companions. Children will have them as tutors, the elderly as caregivers. That means that robots will need to understand right from wrong, pain from pleasure, happiness from sadness.”

There is a catch, however. “Once we do figure out how to integrate all these things, we would likely create a superintelligence that would want to go its own way. I’m not pessimistic by nature, but that’s what worries me.”

On the other hand – who says we aren’t ruled by a superintelligence right now?

About the speaker

Pim Haselager is an associate professor in artificial intelligence at the Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. His research focuses on ethical and societal implications of research and technological practice in areas such as robotics, brain-computer interfacing and deep brain stimulation.