5-minute read - By Peter Wennink, September 5, 2022

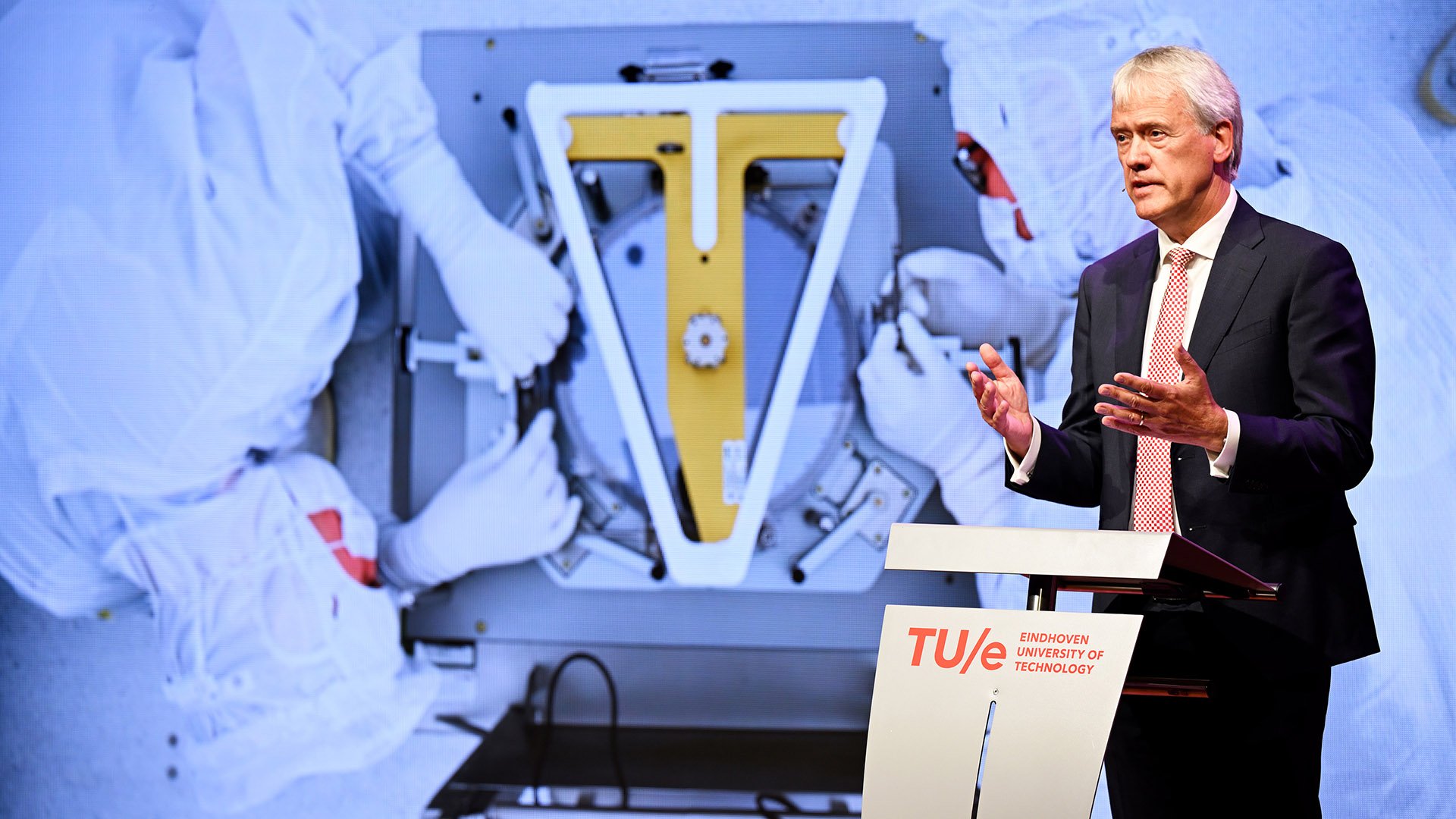

At the opening of the academic year of the Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e), ASML’s CEO Peter Wennink, European Commissioner Thierry Breton, and the Dutch Minister of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy Micky Adriaansens spoke about contributing to Europe’s technological sovereignty and the strategic importance of the chip industry. The following is an excerpt from Peter Wennink’s speech.

The year 2022 marks a special anniversary in the history of technology. Exactly 75 years ago, scientists at Bell Labs created the first working transistor. I say ‘working’, because the idea of a transistor was already documented long before that in the 1920s, but nobody back then had the faintest idea of how to make such a device. It was only through the commitment of Bell Labs to more than 20 years of R&D, their vast melting pot of scientific and engineering expertise, and an incredible amount of trial and error that scientists John Bardeen and Walter Brattain finally pulled it off in 1947. Just a decade later, a young engineer named Gordon Moore co-founded Fairchild Semiconductor, the world’s first commercial chipmaker. As engineers learned how to miniaturize transistors on silicon, Moore famously observed that the number of transistors on a chip would double every year. ‘Moore’s Law’ became an economic driver and innovation catalyst for the nascent chip industry.

Fast forward. Today, my iPhone has Apple’s A15 chip with over 15 billion transistors alone. Our personal lives, family photos, careers, ideas, entertainment, health and fitness are all woven into this chip’s nano circuitry. The rise of ubiquitous computing power has completely transformed our world over the last decades. It has unlocked the potential of technology to create entirely new markets and upset old industries. A world without transistors or chips is simply unimaginable. And whether it’s older chips or the latest and greatest, we live in an age where all chip technology is continuously combined into ever more complex and integrated systems. We need it all.

“A world without transistors or chips is simply unimaginable.”

Chip industry thrust into the limelight

For many years, the chip industry and its key players have remained unknown to the general public. Those days of flying under the radar are over, and the reason is similar to that behind the 1970s oil crisis. Oil was always easy to come by until it wasn't. As a result, it became a strategic commodity. Chips were always readily available until they weren't in 2020. Now, chips are also considered a strategic commodity. Around the world, people are starting to understand the complex and interconnected industry that mass-produces chips – one that acts seamlessly without borders.

The realization that chips are a strategic commodity has also impacted the geopolitical landscape. Governments are seeking to decrease single-sided industrial dependencies and strive for open strategic autonomy. So whether it’s the US, Europe or Asia: world economies are now looking to create chip manufacturing capabilities on their own shores. Technological sovereignty is the aim. From the perspective of risk mitigation, that is understandable. But what is the key to sovereignty in an industry that is as mind-bogglingly complex and globally interconnected as the chip industry?

There can be no technological sovereignty without deep, global collaboration

Breakthroughs in the chip industry are the result of the systemic integration of knowledge and competences across a seamless global network. That network is built on technological extremes, mastered by only a handful of companies. To work towards technological sovereignty, we need to create a global network of mutual dependencies based on strong local relevance. That dependency should not be a problem as long as it’s shared, because when you depend on others, others also depend on you. It’s true: powerful partnerships are not founded on power, but on capability, trust, transparency, reliability and a fair sharing of risks and rewards.

A great example of this is the Brainport Eindhoven region in the Netherlands. It’s the home of tech companies like ASML, NXP, Signify and VDL; of municipalities, big and small; of promising start-ups and scale-ups such as Lightyear, Amber, Additive and Smart Photonics. It also hosts knowledge institutes including the Eindhoven University of Technology, Fontys and Holst Center, as well as hubs and accelerators like the High Tech Campus, Eindhoven Engine and HighTechXL. It’s an incredibly vibrant place, accounting for nearly a quarter of the R&D spend in the Netherlands – truly on the world stage of technology and innovation. This thriving ecosystem can only exist because we trust and help each other through our philosophy of open innovation and a collaborative ‘triple helix’ consisting of industry, government and academia working in synergy with one another. Short communication lines and fast decision-making based on trust mean that we can be agile in a dynamic world. Most importantly, by working together for the greater good of this region, we can learn, grow and stay relevant to the world.

“Most importantly, by working together for the greater good of this region, we can learn, grow and stay relevant to the world.”

Europe is ready for intensified partnerships

This kind of collaboration fits Europe like a glove. It’s no wonder that Thierry Breton, the Commissioner for the Internal Market of the European Union, champions a broad and inclusive discussion about the future of chip manufacturing in Europe. Clearly, Europe is home to a set of unique companies, technologies and knowledge hubs across countries like the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Germany and Italy. ASML would not exist without them. Therefore, Europe has a role to play in building the chip industry of the future, which is set to double in the coming eight years to more than $1 trillion in combined revenue. Looking into the future, there is ample opportunity for an open European ecosystem to stay ambitious, connected and relevant to the global chip industry.

Nurturing engineering talent for the tech megatrends of tomorrow

It’s essential that we keep looking ahead to stay relevant. We need to keep asking ourselves where we’re going and what we need to get there. If there’s one thing I want to highlight today, it’s that the chip industry needs more talented engineers. To fulfill the chip industry’s ambitions, both globally and as a European ecosystem, we need to quadruple the inflow of engineering talent in the coming decade. It’s a massive challenge that stretches across all engineering disciplines and levels. Right now, South Korea, the US, Taiwan and Japan are all investing heavily in chip-related educational and vocational tracks. Therefore, both the Dutch and the European governments need to get into gear to ensure that we’re not left behind. That means working together with industry and knowledge institutes to expand investments in programs around science, technology, engineering and mathematics for the younger generation. In particular, we need to have a laser focus on bringing more female talent into technology. I’m proud to say that the Eindhoven University of Technology can be a model for others in its ambitions and actions, because its research and education helped to put Brainport Eindhoven at the core of the global chip industry, next to places like Grenoble, Leuven, Dresden, Munich, Hsinchu, Seoul and Silicon Valley.

The future is now

Working on the future of the chip industry is brutally hard and complex. But the age of ubiquitous computing has begun. That makes right now the most exciting time to be working in the fields of electronics and computing since the days of Turing, Von Neumann and Moore. And if we do this together, right here in the heart of Europe, then nothing is impossible.

About the speaker:

Peter Wennink

President & CEO of ASML